Orientalism

Art movement

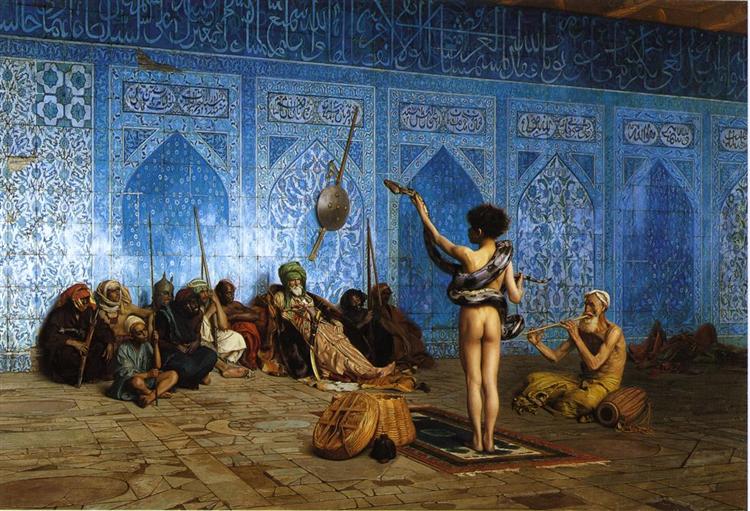

Populating their paintings with snake charmers, veiled women, and courtesans, Orientalist artists created and disseminated fantasy portrayals of the exotic 'East' for European viewers. Although earlier examples exist, Orientalism primarily refers to Western (particularly English and French) painting, architecture, and decorative arts of the 19th century that utilize scenes, settings, and motifs drawn from a range of countries including Turkey, Egypt, India, China, and Algeria. Although some artists strove for realism, many others subsumed the individual cultures and practices of these countries into a generic vision of the Orient and as historian Edward Said notes in his influential book, Orientalism (1978), "the Orient was almost a European invention...a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiments". Falling broadly under Academic Art, the Orientalist movement covered a range of subjects and genres from grand historical and biblical paintings to nudes and domestic interiors.

Beginnings of Orientalism roots to the 15th century. From 1463 to 1479 Venice was at war with the Ottoman Empire, ruled by Sultan Mehmet II. Venice was defeated in several regions and subsequently forced to pay indemnities to continue trading on the Black Sea. In 1479, the Venetian government sent Gentile Bellini, the official court painter for the Doge of Venice, as a cultural ambassador to work for the Sultan. Bellini returned to Venice in 1481 but he continued to include Oriental motifs in his artwork and this can be seen in St. Mark Preaching in Alexandria (1504-1507).

Other artists, including Veronese, began to incorporate similar ideas in imitation of Bellini and as a result, many Venetian artworks survive which depict Middle Eastern subjects. The lasting impact of this can be seen in Veronese's The Wedding Feast at Cana (1563) which depicts Jesus at the center of the table having just changed the water to wine. On his right are Christian guests and disciples in Western clothes and to his left Jewish guests are dressed in an Oriental fashion. This division, identifying Jewish people through Oriental iconography, became a traditional art treatment, lasting into the 19th century as seen in Gustave Doré's engravings in his La Grande Bible de Tours (1866).

France entered the Franco-Ottoman Alliance in 1536 and the alliance, which lasted until 1798, led to several scientific and cultural exchanges. Most notably during the 1700s Turkish items became very fashionable in France and this was reflected in the art of the period. The movement, called Turquerie, was led by artists Jean Baptiste Vanmour, Charles-André van Loo, and Jean-Étienne Liotard, and the style became an element of Rococo art, as seen in Liotard's Portrait of Maria Adelaide of France in Turkish-style clothes (1753).

As a fully-fledged movement, Orientalism began with Napoleon Bonaparte's conquest of Egypt in 1798 and his occupation of the country until 1801, leading to an influx of Egyptian goods into France. Books, too, played a role. The Baron Dominique-Vivant Denon, who accompanied the Middle Eastern expedition as an archeologist, published his Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Égypte pendant les campagnes du Général Bonaparte (1802). It was richly illustrated with Egyptian motifs taken from funeral columns, tombs, and temples, and these influenced French decorative arts and architecture. The French government's Description de l'Égypte (1809-1822) in 24 volumes with illustrations of all aspects of Egyptian life and culture also had a long-lasting influence.

Antoine-Jean Gros was an early pioneer of Neoclassical Orientalism. The official painter for Napoleon, he was commissioned to paint the Emperor's visit to his plague-stricken soldiers in Jaffa, Syria, after his conquest of the city in 1799. Napoleon in the Plague House at Jaffa (1804), was exhibited at the 1804 Paris Salon to coincide with Napoleon's coronation. The work was intended to act as a propaganda tool, arguing for the necessity of French imperialism in Egypt and placing a heroic spin on an ultimately ill-fated campaign. The architectural setting depicted in the painting echoes Jacques-Louis David's Oath of the Horatii (1784), while an Islamic horseshoe arch, the city walls, a mosque, and a Syrian man distributing bread to the sick lend a historical authenticity. Gros's painting exemplified the Neoclassical approach while pointing the way to Orientalism.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres's La Grand Odalisque (1814) was an innovative work in the establishment of Orientalism as a movement and also in its subsequent domination of Academic painting. Commissioned by Queen Caroline Murat of Naples, the painting drew upon traditional images of Venus, but instead of creating an acceptable context for the nude through mythology, Ingres used a Middle Eastern context. In the 1660s the French began using the word odalisque to refer to a concubine in a harem. Taken from the Turkish 'odalik' meaning 'chambermaid' the word in Turkish culture referred to a young female slave, not a concubine but rather a maid, dressed in the same robes worn by male pages. Ingres's title using the word 'odalisque' yoked to the nude, effectively launched Orientalism, and he later returned to the subject, as seen in Odalisque with Slave (1839). Ingres never visited the Near or the Middle East, but like many artists, was what was called 'an armchair Orientalist', relying upon the accounts of others, particularly Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's Turkish Letters (1763). Montague, however, emphasized the contrast between her accounts of the country and the romanticized images produced as part of Orientalism. She notably refuted male portrayals of Turkish baths as sexualized scenes by describing them as, "the Women's coffee house, where all news of the Town is told". Nevertheless, Ingres and other artists took her details and settings as the springboard for their imagined scenes and subjects.

In 1832 Eugène Delacroix went with a diplomatic group to Morocco and, during the trip created several sketches and watercolors. Upon returning to Paris, he subsequently painted Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1834). When the work was shown at the 1834 Paris Salon, the art critic Gustave Plance wrote, "it was about painting and nothing more, a painting that is fresh, vigorous, advanced with spirit, and of an audacity completely venetian". The painting was a ground-breaking model for what would become the widely popular genre of harem scenes and also created a strong interest in Orientalist subjects among Romantic painters.

Orientalism had a noticeable effect on religious painting, as artists sought to lend truthfulness to Biblical scenes. This can be seen in the naturalistic local landscapes that are the setting for Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps' The Finding of Moses (1837) and Joseph Sold by His Brethren (1838). British artists such as William Holman Hunt, a leader of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood traveled to Palestine in the 1850s to employ ethnographically accurate details for The Scapegoat (1854-55) and The Finding of the Savior in the Temple (1854-55) and the Russian Peredvizhniki group employed a Realist approach to their religious scenes set in the Holy Land, as seen in Vasily Polenov's Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (1888) and Ilya Repin's Raising of Jairus's Daughter (1871).

Most famous amongst Orientalist genre painters was Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps. He showed seven paintings depicting everyday life in the Middle East at the 1831 Paris Salon including The Turkish Patrol (1831) and these launched his career. His images, depicting Middle Eastern children at play or merchants in their shops, became particularly popular with the middle class and influenced artists including Delacroix. Other notable examples of Orientalist genre work include Jean-Léon Gérôme's The Mandolin Player (1858) and Nasreddine (Alphonse-Etienne) Dinet's Dancers (c.1904). Demand for Orientalist genre scenes began to spread through Europe leading artists such as the British John Frederick Lewis, the Franco-Austrian Rudolf Ernst, the German Gustav Bauernfeind, and the Italian Giulio Rosati to develop their related style and images.

The harem genre was the most popular of genres, though closely allied with it were scenes of the slave market. Key examples include Giulio Rosati's Inspection of New Arrivals (not dated), Jean-Jules-Antoine Lecomte du Nouy's The White Slave (1888), and John Frederick Lewis's The Harem - Introduction of an Abyssinian Slave (c.1865). These works all depicted the female slave as nude and often emphasized the whiteness of her skin. As Edward Said notes, the popularity of the genre drew upon the idea of the Orient as "a place where one could look for sexual experience unobtainable in the West". Men were not allowed into harems, and so artists, including Ingres, drew upon their fantasies and hearsay accounts in conjunction with European models to create these images. The sense of the male gaze penetrating the forbidden realm of the harem has been interpreted by later art historians like Todd Potterfield as reflecting the Western desire to conquer the land and the realm of 'the other.'

Antoine-Jean Gros led the way in creating dramatic, military works of Orientalism, as shown in his Bataille d'Aboukir (1806), depicting a contemporary battle fought by Napoleon against the Ottoman Empire. Works such as this were popularized through the propaganda campaigns of the Napoleonic government and battle scenes, often depicting heroic French soldiers and actions against Muslim forces, became prevalent. These themes, though reinterpreted within the Romantic Movement, continued into the mid-1800s and they were given impetus by new wars with the Ottoman Empire.

From 1821-1830, Greece fought for independence from the Ottomans, and European artists and intellectuals identified with the Greeks, as seen in Eugène Delacroix's Massacre at Chios (1824). Drawing upon contemporary accounts of the massacre of the Greeks on the island of Chios, the work reflected Romanticism's emphasis upon dramatic suffering and extreme emotional states. In 1830 the French invaded Algeria, and scenes from the protracted war, lasting until 1847, to colonize the country, was also depicted in paintings such as Theodore Chassériau's Battle of Arab Horsemen Around a Standard (1854).

Artists also drew upon classical history, as seen in Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps' Defeat of the Cimbri (1833), a Romantic treatment of the defeat and massacre of the Cimbri tribe by the Romans in 102. Most of these works associated their Oriental subjects and settings with barbaric cruelty and savagery and this is clearly visible in Delacroix's work, Convulsionists of Tangier (also known as Fanatics of Tangier) (1837-1838) which depicts the Aïssaouas, a Muslim brotherhood as a dangerous crowd of fanatics.

The Society of French Orientalist Painters was founded in 1893 with the dual intention of promoting Orientalism and encouraging French artists to travel to Eastern countries. Key figures in the Society were primarily drawn from the Algerian group of painters and included Nasreddine (Alphonse-Etienne) Dinet, Maurice Bompard, Eugene Giradet, Paul Leroy, and Jean-Léon Gérôme. Art historian Leonce Benedite acted as president of the Society from its formation through to his death in 1925. The Society provided a communal focus for artists through its regular Salons and publications, but it was also seen as providing support for colonial rule in North Africa and the Middle East.

Despite the work of such groups, by the end of the 19th century Orientalism was already in decline. The style of Academic art associated with it seemed staid and out of date as new movements, including Tonalism, the Aestheticism, Impressionism, and Post-Impressionism had developed in the latter half of the 19th century. Many of these movements, however, were influenced by Japonism, which was closely related to Orientalism.

Primitivism, too, was informed by the groundwork of Orientalism, as artists such as Paul Gauguin turned to the subjects and motifs of Tahiti, and later artists like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse were influenced by African art. Orientalist-inspired images continued to be made into the 20th century by artists including Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Oskar Kokoschka, and Auguste Macke.

Contemporary artists have similarly referenced the Orientalist works of Delacroix, Ingres, and others, though re-interpreted through the lens of Edward Said's criticism, as well as later feminist and post-colonialist critiques. The Algerian Houria Niati's work recasts the images of Delacroix, as art critic Mary Ann Marger wrote, to dispel "the 19th-century concept of the exotic nature of then French Algeria" and the Moroccan Lalla Essaydi's work also reframes the works of Delacroix, Ingres, and other Orientalists. The French-Algerian Zineb Sedir creates video installations and photographs preoccupied with colonialist displacement and history, while the Turkish Nil Yalter's video artwork portrays the 'disidentified' woman of Orientalism. Şükran Moral 's performance art The Turkish Bath (1997), and Gulsun Karamustafa's Double Action Series for Oriental Fantasies (2000) also critique Orientalism and its stereotypes. Huma Bhabha uses found materials to create her sculptures, as seen in her work The Orientalist (2007) depicting what the artist described as an "Egyptian seated figure" to convey "the character of these different materials using only their textural attributes. The Orientalist is very much a cyborg, with a masklike face that reminds me of the monstrous portrait of Dorian Gray. And giving it that title seemed to link Oscar Wilde's metaphor to Edward Said's critique of Western hubris."

See also Orientalism (style)

Sources:

www.theartstory.org

www.tate.org.uk

Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orientalism